Branding and Jaquet Droz’s automata

It´s a funny thing with brands: we can hardly imagine today that there used to be a time that practically every name of a customer, retailer or group of collectors, could be easily stamped on a dial, movement or case.

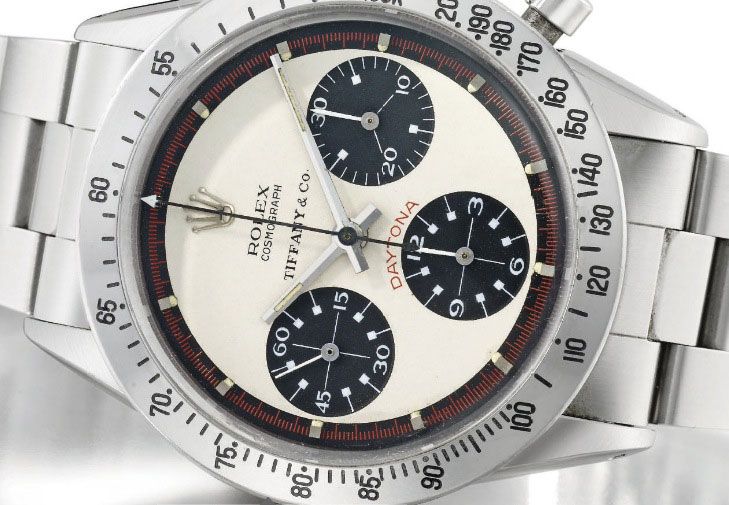

The now prestigious names of established brands were hidden away, either engraved in the movement, the case-back or even unmentioned. The brand, if watch producers even considered themselves to be one, was a modest servant of the public. Jaeger-LeCoultre produced dentist tools and shaving equipment to survive and Patek Philippe watches that are now sought after in auction houses, were proudly bearing the names of the retailers on the dial, above or even sometimes instead of the brand itself. There are also many examples of Rolex and Tiffany & Co like this vintage pre-daytona that somehow didn’t sell that well, back in the days.

These days it´s mainly the brand which is important; all the investments in advertising, branding F1-cars, sponsoring sports teams, polo horses and soirées are not intended to be forgotten to please the customer. No, the brand is the capital and even though every brands tries in its own way to please and convince customers and potential or future customers, there is a need to sell, to make the brand a survivor of these competitive times and to make sure its employees still have a job tomorrow as well.

How different did the world look in 1738 when Pierre Jaquet Droz set up his first workshop in La Chaux de Fonds, where the brand is still located today. Or is it maybe not that different? The young Jaquet Droz (at that time only seventeen years old) realized long before Maslow, Porter, Prahalad and the like came along that a brand was something to cherish. Each movement had a clover leaf engraved in it, as is still the case today, as a symbol of authenticity. Also, the two stars, which are still featured in the logo of the brand more than 270 years later, were designed by him, symbolizing himself and his son, who later joined him in the development of the company. The stars were said to be designed steering clear from the religious symbols; they have seven points contrary to most religious symbols of the 18th century which have survived just as well.

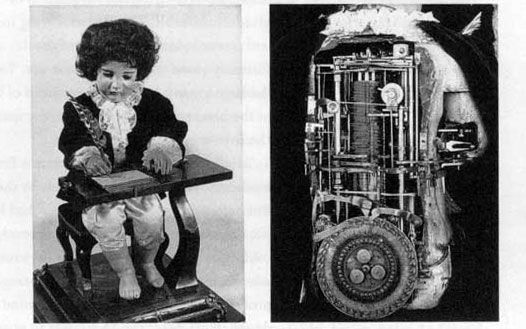

But what maybe said most about the genius of Jaquet Droz, was his focus on the automata, the mechanical predecessors of what we would be calling robots some centuries later. There were, already at this early point in (Swiss) watch making history, many watch makers, but hardly any mechanical wizards who could design and build such a work of art and Pierre Jaquet Droz realized justly this was his entrance ticket to the royal courts in Europe, the Russian empire and other wealthy collectors. Another proof of his commercial feeling: he set up a joint venture, from one of his later workshops in London, with one of the very few trading houses that was already conducting business with the Forbidden City, a bond with China that still exists today.

These automata are still proudly displayed in museums like the one in Neuchâtel and even today it´s hard to understand how someone could develop a technological feat like that without the use of CAD-CAM tools, 3D-printing and computers with amazingly quick processors. In 2009 Jaquet Droz released a modern ‘automata’, The Machine that Writes the Time. However it worked in the 18th century as well: Jaquet Droz travelled the world and was happily invited by the reigning forces of the earth to work his magic, selling watches, both jeweled and classical, in the slipstream.

It´s a pity the history of the brand ended in 1791, when Pierre’s son died, only one year after he died himself. What happened next is another chapter, I´ll tell you more about this fascinating brand soon.