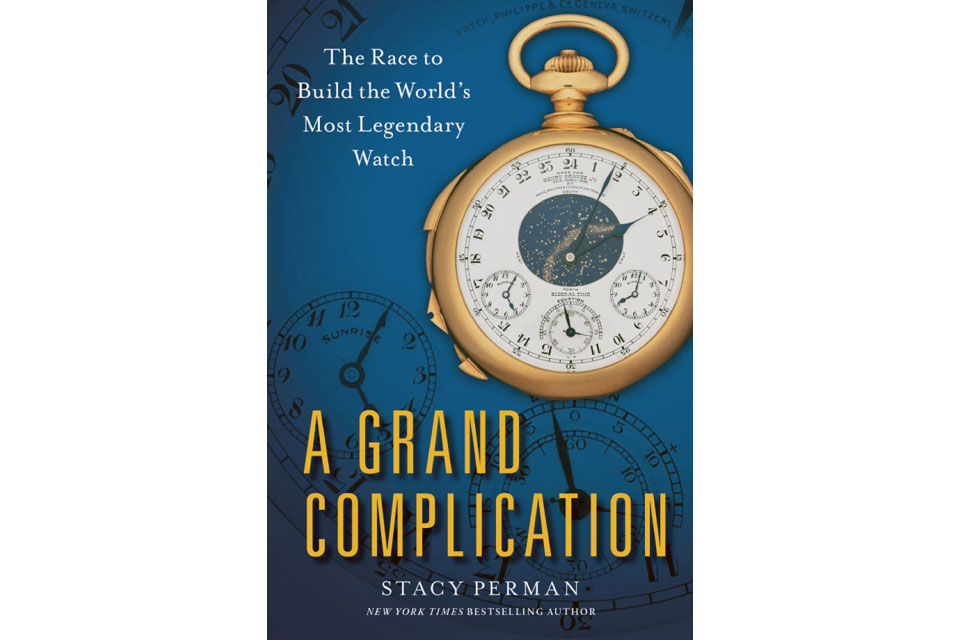

Kicking It Old School: A Grand Complication by Stacy Perman

Give us a book steeped in horological history, featuring names like Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin, filled with tales of watch collecting one-upmanship, and available on Kindle, and we have the perfect summer read. A Grand Complication by Stacy Perman transports us to the worlds of James Ward Packard and Henry Graves Jr. Ward and Graves went head-to-head in a phantom duel to reach the summit of haute horology, the grand complication.

Perman writes, “The two men never met, although their lives intersected. Obsessed with watches, they crossed swords in the dark, each attempting to possess the most ingeniously complicated watch ever produced.” As much a glimpse of America’s Gilded Age of the 1920s as it is a tale of watchmaking frontiers, Perman’s A Grand Complication transports the reader to a bygone age of industrial tycoons and irrational economic exuberance – an age when anything was possible. Match these two well-heeled collectors, for whom money was no object, with their unsurpassed skill of watchmaking greatness, and you have an unbridled tale of discovery.

A watch classified as a grand complication is generally agreed to have at least three complications, and of those three: one must be a timing complication; one must be an astronomical complication; and one must be a striking complication. As Packard and Graves would prove, there is no defined limit to the total number of complications – only the limitations of imagination, technical expertise, and space within the case, and even then, for the times, Patek Phillip could do what seemed impossible. Packard’s penultimate achievement had the gravitas to have its own name in the singular, like Cher or Sting or Bono, and it was known simply as “the Packard.” The Packard was a rock star. Graves, however, had the last word with “the Graves Supercomplication.”

In this book, Patek Phillip takes center stage. There are other names, most notably Vacheron Constantin, but when it comes to the legendary watches, Patek delivered. Ward was an engineer who loved to tinker, and his design talent and aesthetic gave America its premiere luxury vehicle, the Packard automobile. The advertising slogan was that if you wanted to know the value of a Packard car, just ask someone who owned one. Ward’s skill automobile engineering, matched with luxurious style, was also evident in his watch collecting, and Patek became a trusted partner who could take Ward’s technological inspirations, some of them quite idiosyncratic, and translate the concept into a novel creation. No CAD. No CV machine. No instruction manuals. Patek Philippe’s company hand-made these bespoke timepieces relying on the verve of its watchmakers. The results were groundbreaking and stand as monuments to an age of excess, literally towering over time; so much so that when Sotheby’s auctioned the Graves’ Supercomplication in 1999, it went for a cool $11,002,500.

Graves is the Gemini to Ward. Perman differentiates them thusly: “There were men like Ward who built automobiles and men like Henry Graves, Jr., who bought them.” If 1920s author F. Scott Fitzgerald is right in saying, “Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me,” then Graves fits the bill. At the top of the food chain, sat capitalist, industrialist, and monopolist, Henry Graves Jr. Wealth afforded him privilege, and he developed some highly refined tastes. Graves was a private man who loathed notoriety, but he relished the private satisfaction of having what no one else could have – the very best of, well, everything. Watches were no exception. The Graves Supercomplication came on the heels of the Packard with Henry’s directive that it not only be the best, but be better than the Packard. These two patrons pushed Patek Philippe to craft many watches for them, but two watches concluded their silent competition and were the pinnacle of an age: the Packard and the Graves Supercomplication.

The Packard, immediately identifiable by its snowflake minute hand, displaying the difference between mean and true solar time, joined the ranks of the Marie Antoinette or Leroy No. 1 as one of the most complicated watches in history. On the back of the gold case, Ward’s bright blue initials sat emblazoned against a sunburst pattern – a distinctive identifier for his watches. Its movement no. 198023 ran four sub-dials, ten complications, and an astronomical display of the sky, specifically Ward’s hometown of Warren, Ohio. The watch’s ten complications were phases of the moon, mean and true solar time differential, the time of sunrise, the time of sunset (calibrated to Warren, Ohio), the month, day of the week, day of the month, perpetual calendar, minute repeater with three gongs, and rotating celestial chart. If not having the most complications, even fewer than some of Ward’s previous watches, the Packard did have the most complex complications.

The Graves Supercomplication, cue orchestra, wait, drumroll, ok now – is the grand finale with 24 complications! What did this watch not do? Graves originally paid a figure close to $15,000 for it ($265,000 in today’s dollars) and waited eight years to receive his prize, and when he took possession, he was the undisputed victor of all time, the best.

Perman’s book is a watch collecting, and thus watchmaking, odyssey where two men, possessed by the collecting bug, traverse an ever more sophisticated, truly ever more complicated, ground. The trajectory from these men’s beginning purchases to the final destination of the Packard and the Graves Supercomplication is a wide-angle lens panorama of the Jazz Age, America’s industrial aristocracy, and the excellence of Swiss watchmaking. By hearkening back to a time of more, Perman shares the limitlessness of human aspiration.