State of the Industry – Who Does or Doesn’t Have an In-House Chronograph?

Not so long ago, just a handful of manufactures had the resources to produce mechanical chronographs… but the situation has drastically changed.

If the chronograph is one of the most popular complications, it is also one of the most complex types of movements to manufacture. Not so long ago, just a handful of manufactures had the knowledge or the financial resources to produce their own, in-house mechanical chronograph calibre… but the past 20 years have witnessed the birth of an impressive number of self-developed movements.

During the 1970s, new accurate quartz movements gained popularity and plunged the Swiss watch industry into a deep crisis. Sales of mechanical watches declined sharply, production of mechanical movements was reduced to a trickle, and many Swiss watchmakers went out of business. Zenith is an eloquent example of how stock and production capacities were destroyed (and saved by an act of disobedience for El Primero – read the history of this iconic chronograph here).

Following the renaissance of mechanical watchmaking in the 1980s and 1990s, brands massively invested in movement development and production facilities. At the time, very few watchmakers were actually producing movements. Most of the industry was sourcing from the same movement manufacturers: ETA for industrial movements and a few high-end makers such as Frédéric Piguet, Lemania, Zenith or Girard-Perregaux, to name a few.

To ensure a steady supply of movements and boost their image, brands started to develop their own mechanical movements. These started with standard 3-hand movements but soon the need for the king of complications became apparent. In the late 1990s, only a handful of manufacturers were producing chronograph movements internally. Watch brands mostly relied on outsourced, standardized movements. This was a serious challenge because developing a chronograph movement is no small feat. It was – and still is – regarded as a crowning glory for a manufacture. Most watchmakers will tell you that apart from a minute repeater, the chronograph is the most complex movement to develop.

Fast forward 20 years and today there is an abundance of in-house chronograph movements.

Of course, there are large movement makers like ETA with the ubiquitous 7750 or Sellita with the SW500-1 (an alternative to the 7750). There are also smaller companies such as La Joux-Perret, Vaucher, Agenhor or Concepto. Zenith sill delivers chronographs to LVMH brands. Also, Dubois-Depraz manufactures chronograph modules that are coupled to mechanical movements – even though it just presented an integrated chronograph. However, most of today’s major brands have their own chronograph movements. Here’s a chronology of the in-house chronograph since the late 1990s…

Note: The list gathers some of the largest brands that have presented in-house chronograph movements. There is no official standard for an in-house watch movement and the Swiss watchmaking industry is an intricate ecosystem. Breguet and Blancpain are not included as Swatch Group acquired Blancpain and Frédéric Piguet in 1992 – Breguet and Lemania in 1999. Frédéric Piguet and Lemania, two prominent movement makers were integrated into the Blancpain and Breguet manufactures. We have chosen to present all movements as announced by brands even if within groups, some movements present obvious similarities. For more information about chronographs, you can read our technical perspective here.

A. Lange & Söhne Datograph – 1999

The first A. Lange & Söhne chronograph of the modern era is the benchmark for a high-end chronograph. The Datograph combines everything a purist wants, including exceptional finishing. Among other notable feats, the Datograph incorporates a flyback mechanism, precisely jumping minutes and an outsized date.

Quick facts: calibre L951.6 (Dato Up/Down as of 2012) hand-wound chronograph – 30.6mm x 7.9mm – column wheel and horizontal clutch – 46 jewels – 18,000 vibrations per hour – 60h power reserve

GLASHÜTTE ORIGINAL PANORETROGRAPH – 2000

Fast on the heels of A. Lange & Söhne’s Datograph, Glashütte Original wowed the stage with its PanoRetroGraph, a highly complex flyback chronograph complete with a 30-minute retrograde countdown counter equipped with a chime. Removing the retrograde and chiming, it would become the superb and unconventional PanoGraph from 2002.

Quick facts: calibre 61-03 (PanoGraph) hand-wound chronograph – 32.2mm x 7.2mm – column wheel and horizontal clutch – 41 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 42h power reserve

ROLEX Calibre 4130 – 2000

At Baselworld 2000, Rolex presented its in-house chronograph movement to power the iconic Daytona – which had previously relied on a modified version of the Zenith El Primero (dubbed 4030 at Rolex). The 4130 is a benchmark for the robust, still industrially-made automatic integrated chronograph.

Quick facts: automatic chronograph – 30.5mm – column wheel and vertical clutch – 44 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 72h power reserve

JAEGER-LECOULTRE JLC 751 – 2004

This modern twin-barrel automatic chronograph runs at 28,800 vibrations per hour for a 65h power reserve. It features a column wheel and vertical coupling and was launched inside the Jaeger-LeCoultre Master Chronograph.

Quick facts: automatic chronograph – 25.6mm – column wheel and vertical clutch – 37 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 65h power reserve

IWC 89000 – 2007

Since IWC had long used Valjoux-based chronographs, the brand decided to introduce the 89000 family in 2007. The 89000 is a 30mm flyback integrated chronograph running at 28,800 vibrations per hour, with 68h power reserve, column wheel, rocking pinion and Pellaton winding system. It can be combined with various additional functions (including perpetual calendar).

Quick facts: automatic chronograph – 30mm – column wheel and rocking pinion – 40 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 68h power reserve

PIAGET 880P – 2007

Piaget presented its first in-house chronograph in 2007, with the 880P. This integrated movement, with column wheel, will be the base to develop the 883P, the world’s thinnest chronograph (until recently).

Quick facts: automatic chronograph – 26.8mm – column wheel and vertical clutch – 35 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 50h power reserve

PANERAI P.2004 – 2008

Presented in 2008, the Panerai P.2004 is a hand-wound, single push-piece chronograph remarkable for its large diameter and because it incorporates three barrels resulting in impressive 8-day power reserve. It relies on a column wheel and a vertical clutch.

Quick facts: hand-wound chronograph – 30mm – column wheel and vertical clutch – 29 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 192h power reserve

PATEK PHILIPPE CH 29-535 PS – 2009

In 2005, Patek Philippe presented a superb split-second chronograph, calibre CHF 27-525 PS. Manufactured in-house, the calibre was inspired by an old Victorin Piguet Ebauche ref. 5959. The long-awaited first modern Patek Philippe classic in-house chronograph didn’t make its debut in a men’s watch but in a ladies’ watch (reference 7071). The superb CH 29-535 PS is a traditional design with column wheel and horizontal clutch. It was the first to bear the Patek Seal. It made its masculine debut in 2010 when Patek presented the reference 5170, which replaced the reference 5070 based on a Lemania blank.

Quick facts: hand-wound chronograph CH 29-535 PS – 29.6mm – column wheel and horizontal clutch – 33 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 65h power reserve

HUBLOT UNICO – 2009

Presented in 2009, the Hublot Unico stands out with its chronograph mechanism positioned dial side. It is modernly designed to fit with the look of Hublot watches but its architecture is traditional.

Quick facts: automatic chronograph HUB 1242 – 30mm – column wheel and double clutch – 38 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 72h power reserve

BREITLING B01 – 2009

Unveiled in 2009, the Breitling B01 is modernly designed with column wheel and vertical clutch. The B01 calibre is now shared with Tudor watches and used in the Black Bay Chronograph.

Quick facts: automatic chronograph Breitling B01 – 30mm – column wheel and vertical clutch – 47 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 70h power reserve

TAG HEUER Calibre HEUER 01 – 2009

The in-house label of TAG’s calibre 1887 generated controversy when it was introduced because it was based on a Seiko movement – that was manufactured internally by TAG Heuer, though. It became the Heuer 01 when the new Carrera collection was introduced. It was followed in 2013 by the calibre 1969/CH-80, which was this time a real in-house chronograph movement (development included).

Quick facts: automatic chronograph calibre 1887 or Heuer 01 – 29.3mm – column wheel and oscillating pinion – 39 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 50h power reserve

OMEGA Calibre 9300 – 2011

Knowing the industrial organization within the Swatch Group, one could argue for hours about the first ‘in-house’ chronograph at Omega (taking the example of the 1861, which is based on Lemania blanks). This is why we have picked the calibre 9300, the first true in-house integrated automatic chronograph with Co-Axial escapement. Presented in 2011, the 9300 features a silicon balance spring, a double barrel, a column wheel and vertical clutch.

Quick facts: automatic chronograph Omega 9300 – 30mm – column wheel and vertical clutch – 54 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 60h power reserve

CHOPARD 03.05.M – 2012

Chopard has been using in-house movements for a long time with its L.U.C. line of high-end watches. However, when it comes to classic Chopard watches, it’s only with the Chopard Superfast collection that the brand started to use an in-house automatic chronograph. The calibre 03.05.M is a COSC certified column-wheel chronograph with original openworked bridges.

Quick facts: automatic chronograph 03.05.M – 28.80mm – column wheel and vertical clutch – 45 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 60h power reserve

ULYSSE NARDIN UN-150 – 2012

In 2012, Ulysse Nardin bought the Ebel 137 Chronograph. It was renamed UN-150 and reworked in-house with several updates including a silicon hairspring (seen below with the oscillating mass).

Quick facts: automatic chronograph – 31mm – lever chronograph – 25 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 48h power reserve

CARTIER 1904-CH MC – 2013

The Cartier calibre 1904-CH made its debut on board the Calibre de Cartier Chronograph. It is a twin-barrel movement with column wheel and vertical clutch.

Quick facts: automatic chronograph – 26.8mm – column wheel and vertical clutch – 35 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 48h power reserve

GIRARD-PERREGAUX 3800 – 2013

Produced in rather limited quantities so far, the first GP modern integrated in-house chronograph is based on its 3000 series. It features a traditional horizontal clutch and column wheel as well as jumping minutes. Before its development, the brand relied mostly on Dubois-Depraz modules as well as a small, original in-house modular chronograph with its column wheel visible dial side.

Quick facts: hand-wound chronograph – 25.6mm – column wheel and horizontal clutch – 31 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 58h power reserve

VACHERON CONSTANTIN 3300 – 2015

Vacheron Constantin’s first in-house chronograph movement made its debut in the Harmony collection. Bearing the Hallmark of Geneva, it features a classic column wheel and a horizontal clutch and is a mono-pusher hand-wound calibre.

Quick facts: hand-wound chronograph – 32.8mm – column wheel and horizontal clutch – 35 jewels – 21,600 vibrations per hour – 65h power reserve

FREDERIQUE CONSTANT FC-760 – 2017

Frederique Constant’s in-house chronograph stays in line with the concept of affordable luxury, with a retail price just over EUR 3,500. This modular flyback chronograph features an original star-shaped column wheel and a new type of clutch based on a swivelling component with two toothed pinions.

Quick facts: automatic chronograph – 30mm – star-shaped column wheel and specific clutch – 54 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 38h power reserve

AUDEMARS PIGUET 4400 – 2019

Until 2019, AP only manufactured small quantities of high-end, complicated chronographs in-house – in the APRP manufacture. However, the brand relied mostly on outsourced, modular chronograph movements for its simpler watches… until the launch of the high-grade 4400 calibre that debuted with the Code 11.59 collection. This integrated column-wheel, vertical clutch movement was developed as part of a new family of movements together with the AP 4300 automatic base calibre.

Quick facts: automatic chronograph – 32mm – column wheel and vertical clutch – 40 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 70h power reserve

PARMIGIANI FLEURIER PF362 – 2019

Following the presentation of the superb Chronor split-seconds chronograph in 2016, Parmigiani unveiled the calibre PF362 on the same base. This shaped calibre is a high-frequency chronograph with vertical clutch and column wheel.

Quick facts: automatic chronograph – 39.7mm x 31.9mm – column wheel and vertical clutch – 32 jewels – 36,000 vibrations per hour – 65h power reserve

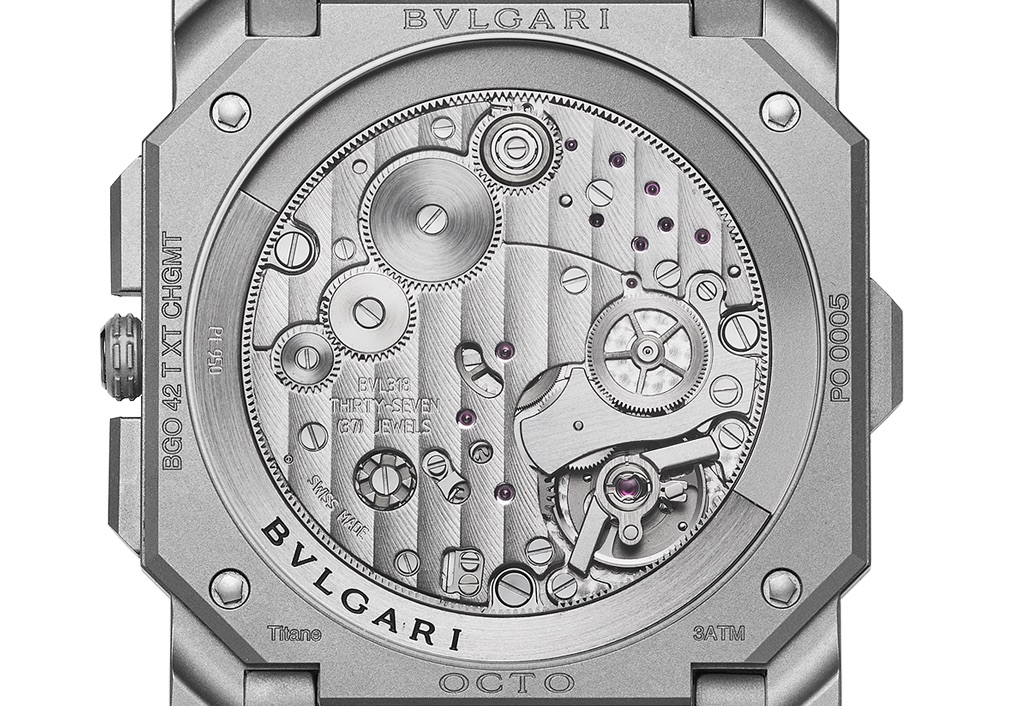

BVLGARI BVL 318 – 2019

Part of the impressive series of records of the Bvlgari Finissimo saga, the BVL318 is the world’s thinnest chronograph (and automatic chronograph) at just 3.30mm thick. To achieve such thinness, the movement is wound by a peripheral rotor while the large diameter has allowed all functions to be arranged horizontally.

Quick facts: automatic chronograph – 37.2mm – column wheel and horizontal clutch – 37 jewels – 28,800 vibrations per hour – 55h power reserve

47 responses

This is getting bookmarked. Wonderful stuff.

Excellent list! No love for Seiko?

Would F.P. Journe’s sublime 1518 qualify for the list? I suppose maybe not because it’s not a large manufacture. But it’s a beaut all the same.

How about the Roger Dubuis chronograph in Monagasque and Hommage? Only micro rotor Chrono I’m aware of… although maybe because it appears they’ve stopped producing, after viewing web site.

@Gil. Thank you!!!

As for your question, we’ve only listed chronograph, no rattrapante here.

We love Seiko of course. This list will evolve as we’ll find more of them 🙂

I know what I’m reading tomorrow with my morning coffee and I’m so looking forward! Thanks a million Monochrome for such an amazing article.

great informative writing work, which was really missing in such an updated version…very useful, thank you…

ok you literally did not not the first automatic chronograph and on the most iconic movements of all time “the Zenith El Primero”

Great comparison. Saved in Pocket for later as well.

Great article, thanks! Puts some manufacturers more into perspective for me.

The montblanc nicolas rieussec? Wasn’t that in-house?

Lots of lovely stuff here which shows the combination of beauty and engineering high end mechanical watches can deliver.

Excellent article.

But, it also shows that the Valjoux’s Lemania’s and Zenit’s played an important role in some very well known high luxury and expensive brands.

Aside from the aforementioned El Primero needing it’s own entry, why not Seiko? They have both mechanical and Spring Drive chronos…

Fascinating article, some of these as well as being clever are absolute works of art, particularly the A. LANGE & SÖHNE DATOGRAPH – 1999. I do wonder however do any of these actually get used after they have been played will when first bought?

@Brice

Ah, of course yes, it’s a rattrapante.

Please do a battle of the high-end rattrapantes sometime soon.

And please do a battle of workhorse movements so we can understand why >95% of mechanical watches do perfectly well with basic calibres like the 2824, 6R15 etc.

I read an interesting article by a knowledgeable watchmaker who made the argument that the 2892 is actually better then the 3135 which displayed an engineering weakness with which he was uncomfortable. A weakness which the previous Rolex calibre did not have.

The major real-world performance difference between these exotic movements and the standard ones is the amount of time that is spent on setting them up. That is one aspect of Rolex which I cannot fault. I assume Lange et al do the same.

@JD thanks 🙂

@Izhik z Thank YOU

@JAGOTW

I think of the 3135 as a basic movement, just tested to extremely high standards. I’ve certainly always regarded the high-grade 2892s to be every bit as respectable. Wasn’t the movement that preceded the 3135 the one that Walt Odets infamously savaged? I suppose that may have been more the dog-dirt finishing than the architecture itself, though.

Anyway, I echo your wish for a workhorse battle.

Excellent article, didn’t know so many manufactures had developed the capabilities; and some of the top brands are more recent.

El Primero??

Hi Gil. I believe the… 3130 had a more robust central pinion that resulted in less efficient winding. Rolex sacrificed this for easier winding but the rotor pinion is now a common repair.

The problem is the definition of basic. And don’t let Rolex hear you say that! 😉

Haha!

That’s useful info, I didn’t know that. I wonder if that’s an issue with the 3235 also.

Yeah, me too. It can be hard to read through the Marketing Speak and sometimes it takes ages for that kind of teardown to be put online and even longer to find it in the dark recesses of The Web. I would not feel confident to simply look at a picture and make assumptions. They are a lot of work, these side-by-side analyses if done right and sadly there’s not too much reward for doing so. And this is where we get to the nuts and bolts.

I recently had a look at a Shanghai A581; a re-issue of a watch and caliber from 1958. Basically a re-release of the “standard” movement that was developed to provide The Proletariat with a reasonably accurate, reasonably robust timepiece. Now that IS a basic movement! I don’t even think it has shock protection! I held it close to my ear and wound it. It sounded fantastic; like a “real” watch, with that lovely micro-ratchet sound of metal against metal and it rang clearly because of the basic housing and minimalist case. To my eye I reckon it was going at about +6 or 7 s/day in a static position. Perfectly acceptable. It got hundreds of millions of people to work on time for decades and as a piece of watch-making history, it might not be worthy of a safe and lint-free gloves, but it is important.

Anglage, perlage, clos-de-how-your-father. These are NOTHING to do with horology. It’s important for us all to remember that when we’re drooling over masterpieces such as those above. I sincerely wish Lang would produce a movement without all that fluff in a closed caseback. It would be purer.

You would absolutely love the Spezichron (sporty cushion square case) or the Spezimatic (formal round case) that the Glashutte Uhrenbetriebe GMBH made under Soviet control in the ’70s/’80s. The Spezichron is the watch that the current GO Seventies is a sort of tribute to. There’s loads of variations of them out there that are a steal.

Don’t you knock the guilloche, though. The master of masters himself saw it as an artisanal perfection of the entire craft from A-Z, and as a way to also improve the legibility of the watch. It deserves its place.

But yeah, perlage and anglage are just go-fasta stripes.

I did a quick image search of the spezis and they look remarkably similar to the SH watch!. A few of the variants strongly remind me of the original Mido Commander too. I do like that style very much. Do you have any idea which movements they used?

I don’t, sorry. Never looked into it, only knew that they were mechanical and not quartz. I’ll have an investigate today.

Had a delve, it seems to be either the GUB Cal 74 (no date) or Cal 75 (date) that the Spezimatic models have. The Spezichrons had a slightly improved movement – the Cal 11-26 (date) or Cal 11-27 (day and date).

Info on Cal 74: Google ‘Glashutte Cal 74’ and the first hit should be for glashuetteuhren.de – that has all the info and you can translate to english on a bar at the top of the page.

Info on Cal 75: ht*ps://17jewels.info/movements/g/gub/gub-75/

Info on Cal 11-26: ht*ps://w*w.watch-wiki.n*t/index.php?title=VEB_11-26

There’s also info on 11-26/27 from glashuetteuhren.de if you google ‘GUB kalibergruppe 11 spezichron’, then should be first hit, translate again from the bar at the top of the page.

Apologies for the asterisks, I fear Frank’s patented link defence would have liquidised the post otherwise. Also, one rather nice thing to remember about GUB is that it had Lange & Sohne guys working for them, grouped together with the rest of Saxony’s best.

In addition to Seiko, a mention of Habring may be in order.

Great article, as usual, otherwise.

Thanks Gil! I’m currently having a…”discussion” with someone on my phone about this very topic. She wants a new “nice” watch but won’t consider anything that isn’t Rolex because…well she doesn’t know. She just “knows” that Rolex make the best watches.

sigh…

Rolex are good, but she needs…corrected, if I may be so bold sir.

You may. 🙂

She read a few articles and we just went watch shopping. We tried on Nomos, Breitling, Rolex and JLC. After trying on a Reverso she got a bit of perspective. Both Rolex boutiques were bereft of steel models. Lots of empty cases. Rolex have a problem. There was a massive case with ONE Datejust in it. We tried it and rejected it but at the same time another salesperson was talking about the same watch to another customer! Fighting over a steel Datejust while about 100 gold and diamond monstrosities get ignored.

What a farce.

It is daft, that’s for sure. The Reverso is almost the perfect red pill for her to open her mind. I’m trying to think of something as fine a quality as that in the price range, and apart from maybe Cartier’s smaller Santos and Tanks, she’d be hard-pressed to do better.

Yeah, The Reverso is like the kobe beef of watches. Everyone knows it’s great, but they try straw-fired pheasant or bone marrow and the like to be different. But when all’s said and done, a great piece of beef leaves nothing to be desired. I had BBQ in rural Japan once and it was ridiculously good. Still wouldn’t play polo wearing one!

Japanese food is incredible. I was there about 15 years ago staying mainly in and around Tokyo with a couple of days in Kyoto. Tried everything from chicken cartilage to still-gasping fish, to raw horse, to sea cucumber and some fermented awfulness that even the sake couldn’t help…but I never tried the native Kobe. Regret that.

…Which is apt as I’ve yet to own a Reverso.

I lived there for a year. Had o-toro any time I wanted. Had great sushi practically every day for months. Local supermarket had all the great wines. Was great.

Warning: don’t go on a 3 day camping trip in summer and forget to put your sushi in the fridge!

She now wants a Nomos and only a Nomos. I did a good thing!!

You certainly did. A great introduction to well-made watches that she can take pride in; she can always get a Rolex later down the line, or even a Reverso. Perfect thing about Nomos is that she’ll learn a bit about Glashutte, that tiny little place where almost everyone’s a watchmaker, and hopefully spurns her into being fascinated by the whole horology thing.

One of us. One of ussssss.

B-)

Why isn’t PP CH 28-520 C here?

@MsThu, we have listed brands with their first ‘in-house’ chronograph, starting from the late 1990s, not all chronographs for every brand. This also explains why El Primero is not included in the list although it is mentioned several times in the article.

When did Zenith make their first in-house chrono?

El Primero was developed in 1969