Swatch Group’s Powermatic Movement, a Powerful Entry-Level Engine

The Powermatic movement, the silent hero that gives power to the people.

Have you ever wondered how Swatch Group brands like Tissot, Certina, Hamilton and Mido can make reliable, robust and accurate mechanical watches of good quality at very reasonable prices? Take a look inside the cases and you’ll see the answer ticking there: the movement that seriously raises the bar for the entire industry. Its name: Powermatic. Entry-level, yes, but without being cheap.

MONOCHROME is more about the high-end segment of the watchmaking industry; the complicated movements, the perpetual calendars, the chiming watches, the exotic regulators, the independent watchmakers who create the most complex indications or tell the time in unusual ways. But this time, we dive deeper into one of the workhorses that drive Swatch Group growth, the Powermatic movement.

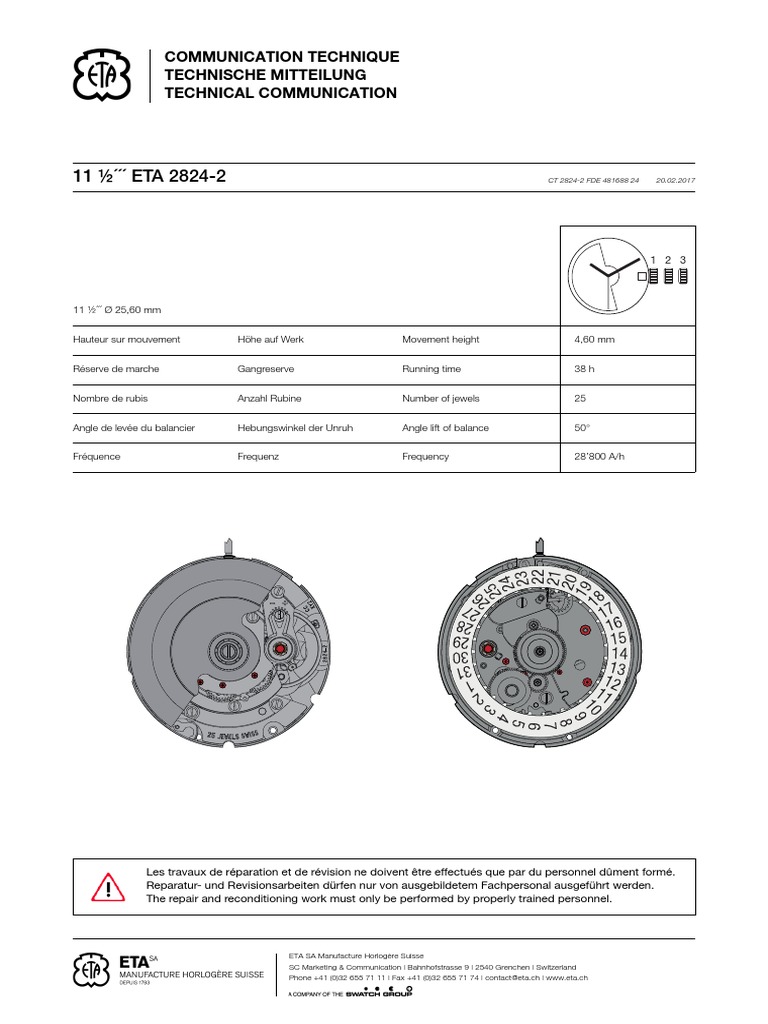

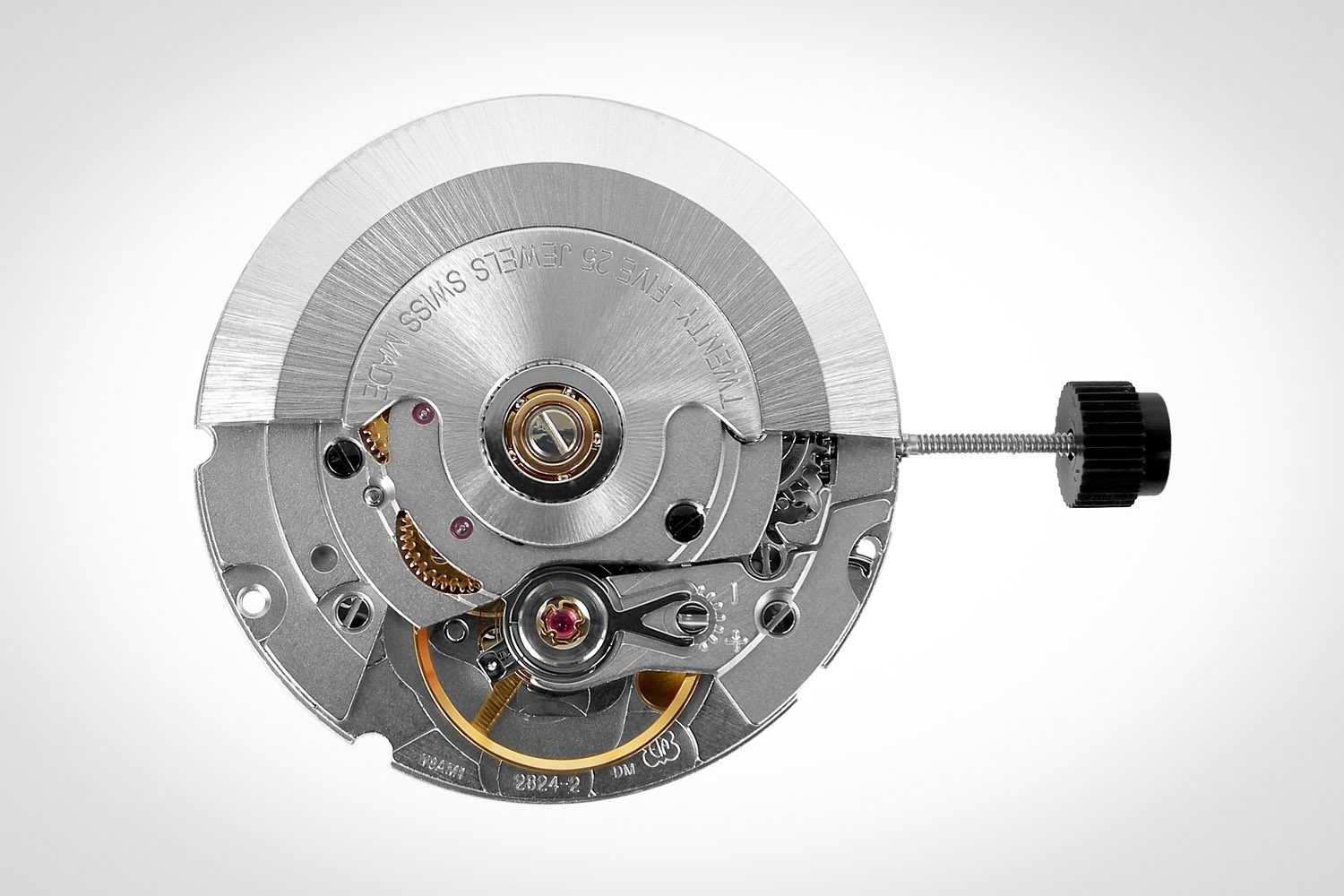

The predecessor – ETA 2824-2

The Powermatic movement, or ETA calibre C07.111 as it is officially known, was introduced in 2011, but its roots go way deeper. Its base was the ETA 2824-2, which itself was an evolution from the classic Eterna 1427 movement, that at the time of its introduction in 1955 was the world’s thinnest automatic movement. Eterna, back then, was a world leader of automatic movements – its first use of ball bearings in the Eterna-Matic in 1948 really changed Swiss watchmaking forever. ETA was set up in 1856 as a separate movement-production branch from Eterna and the two companies were forced to split in 1932 by the Swiss government. Still, ties remained strong and in a way, the biggest workhorse in watchmaking history, the ETA 2824-2, was their love child.

Both ETA and Eterna were never the artisans; they’ve always been the industrial engineers. But the fate of both companies couldn’t be more different. Eterna is currently in a very unfortunate position and struggling to stay alive, while ETA is the thriving movement production powerhouse of Swatch Group. The position of ETA is so strong it had to (and still has to) fight legal battles against misusing its monopoly position. The ETA 2824-2 movement is the stronghold of the company, the best-known and most widely used mechanical movement of all. It is reliable, robust, accurate and quite cheap to produce in mass. It has set the bar of what a basic mechanical movement should be.

The need for evolution

Still, ETA and Swatch Group, in general, felt the need to improve their product in order to keep ahead of the competition. And with good reason. Despite its success, the 2824-2 does have some shortcomings. Its power reserve, for example, is not impressive (38 hours). The movement is also so common that it is hard to differentiate Swatch Group brands from other competitors in the market. But the most problematic of all: the patent of the movement was expiring. And that made it a very high priority for Swatch Group to come up with a better and even more efficient movement. The initial request came from different brands in the mid-price segment of Swatch Group (Tissot, Certina, Mido and Hamilton) and ETA was set to lead the development.

When exactly Swatch Group took the decision to take the big step to thoroughly improve its powerhouse is not exactly known, as Swatch Group does not communicate about development work. So we can only make an educated guess here. Knowing that the movement was first introduced in 2011, and the target was to ensure an industrial process – which means that an adapted infrastructure had to be built up before starting even with small series – it must have been around 2005-2006. Exactly the time that the company was starting to see the first legal problems from Nicholas Hayek’s 2002 declaration to cease supplying ébauches to companies outside the group.

Now, that tells us quite a lot about the importance of this movement. The Powermatic wasn’t only an evolution of the 2824-2, it was created to make its predecessor, with its patent expiring, obsolete. And in a way, it did exactly that.

Technical goals and achievements

When you first look at the Powermatic movement, you might be tricked into thinking it is just a reworked ETA 2824-2, with some improvements. But that is just not true. Every little piece was re-evaluated and if possible improved. In fact, the parts that were kept from the 2824 were the components that are not directly connected to the regulation organ and the barrel. The ones that were already produced in a very efficient way, have been kept. The number of components is also identical. The movements are also made and assembled in the different locations of ETA in Switzerland.

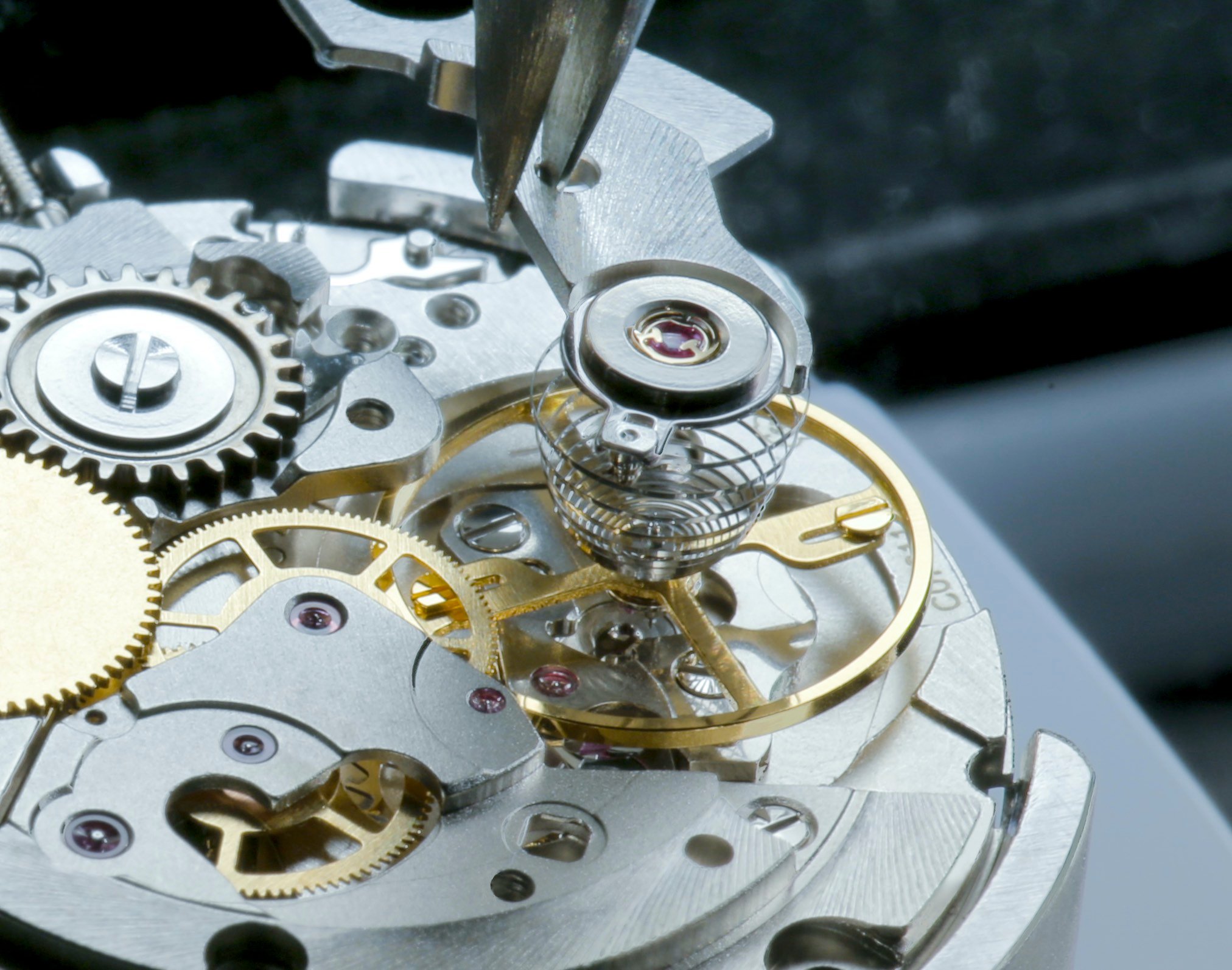

The target, as a spokesperson from Swatch Group told me, was to keep the compatibility of the 2824, and to evolve quite a lot at the same time. The main targets were to improve the power reserve and reduce the manual work to ensure accuracy and stability by industrial processes. This is accomplished in some very interesting ways using the most modern production techniques. If you look carefully at the balance wheel construction from the Powermatic movement, you’ll see it is different from normal constructions, it seems to be a ‘module’. The spokesperson told me: “The forks and that way the connected inaccuracy, especially at low power reserve, for fine adjustment have been removed. The whole design allows direct and automatic production of the whole regulation group without manual operations.” This is no less than a silent revolution in watchmaking, done with the most modern techniques. In fact, the entire idea of having an escapement with no regulator has been replaced by setting the rate with a laser in the factory. And that, indeed, is a lot more efficient and precise.

Exactly how precise is shown by the number of chronometers mid-segment Swatch Group brands have been able to produce and at what prices. A Tissot Chronometer only costs around CHF 200 more than a ‘normal’ mechanical watch. Asked if there is any technical difference between the ‘normal’ Powermatic movement and the chronometer-certified, the answer is clear: basically none. As the process is industrial and without manual regulation, the forkless regulation can be brought much easier to the chronometer level at much more affordable costs. The entire regulating organ is put in the movement as one ‘module’, thus also reducing repair costs. If your balance wheel is broken, this entire module will be replaced by a new one. Indeed, your watch is not getting a pacemaker, you’re getting a completely new heart. Lovely.

The biggest improvements: power, materials and efficiency

As mentioned, one very big improvement with the Powermatic compared to the ETA 2824-2, is the power reserve. A normal ETA 2824-2 will run for about 38 hours before it stops; the C07.111 delivers its energy for 80 hours. That is not only achieved with an improved spring barrel; it also got a new construction concept that works more efficiently than its predecessor from 1961. In addition to that, and thanks to modern manufacturing processes, the frequency has been reduced to 21,600vph (instead of 28,800vph), without affecting the accuracy of the movement. But this lower beat contributes to the longer power reserve too.

And that also improves the versatility of the base movement. Thanks to its larger power reserve and modest size, it is capable of carrying more complications. Some add-ons have already been introduced, such as a day-date, GMT and a big date, but bigger and more complicated ones will certainly follow in the future. Although Swatch Group obviously doesn’t communicate this information, anyone who knows something about watches is invited to make an educated guess.

The differences with the ETA 2824-2 go even deeper; it’s not even made from the same material. Exactly which materials have been used in the different Powermatic calibres, Swatch Group doesn’t tell, but our information tells us that the steel alloy is a bit different from usual movements, the so-called ARCAP alloy, which is anti-magnetic. (For the real metal-heads among us: it is made up of a combination of nickel, copper, cobalt, tin, lead and zinc.) In some cases, ETA even adds plastic materials to the movement.

One thing Swatch Group does share and is very proud of is the use of a silicon escapement in the latest Powermatic calibres. It was first introduced earlier this year, in the Swatch Flymagic, and later also in the Tissot Powermatic 80.

This improvement gave the watch anti-magnetic properties, and it reveals how consistently ETA is working on the development of this movement. If the improvement of the Powermatic continues at this rate, it will make the 2824 feel obsolete within years, and Swatch Group will have reached its goal of staying ahead of its competitors on the technical front. Competitors whom it was forced to supply and, in Hayek’s words, subsidize.

The downside of the Powermatic

Of course, this industrial take on watch movements has its downside. It is, for example, not the best-looking movement in the world. Its finishes are decent and every brand can add its own detailing on the rotor. It shows the most basic of all mechanics in watchmaking, and that’s it. There’s no engraving, almost no decoration, no perlage, no Geneva stripes… almost nothing. In any case, this has no effect on the mechanical properties of the movement. Still, most Powermatic-using brands offer glass casebacks in their collection, because they know their target group is admiring the mechanics anyway. The Powermatic opens the doors to the world of horology.

The Powermatic is not a revolutionary movement in the way the Calibre 11 or the El Primero were. It is more a popular revolution, in the way the first 1983 Swatch was. It might not be as cool as that first plastic piece, but it’s definitely made with the same intention of bringing Swiss power to a larger audience, without compromising the quality and precision.

Bringing power to the people – Hayek style

These Tissot, Certina, Hamilton and Mido watches are always of the my-first-watch kind. These watches have just enough detailing to be considered a luxury watch, and with their neat finishes, robust quality and glass casebacks, they steal thousands of hearts every year from aspiring watch collectors. With the Powermatic, that heart is still replaceable, but without a doubt that love will lead those new watch lovers to buy even better and more expensive watches.

Hopefully, for Swatch Group that will be an Omega, or Breguet, or Glashütte Original, or Blancpain or even Jaquet Droz, but it could just as well be a Patek Philippe. Now that would definitely be the kind of subsidizing the watch industry Nicholas Hayek would have approved of.

21 responses

También pueden explicar que este modelo tiene instalado componentes sinteticos. Seguramente para que pese menos!!.

Se atrasan bastante.

Reloj obtimo si lo compras por menos de 430.00€.

Interesting to see what is going on in the real world for a change .

Well, that ETA is the Chevy ‘small-block’ of watch industry. Btw. Louis Chevrolet (the founder of the US motor company) was a Swiss.

My Tissot Seastar 1000 powermatic 80 is one of the best watches I own..

I found this very interesting for someone who has little knowledge of watch movements

As someone who do the services on his own watches, I don’t like this piece. Without a regulator and with a silicon spring it will be much more difficult to set and basically it will be like any Chinese 21j that once giving bad performance you just replace.

Yes, I understand that a silicon and therefore amagnetic spring is better, but still…

Plus it’s 21.6kBPH: well at this point for a thin movement I’d just go for a Miyota 9015 which, at least, has a better smoother second hand move being it a 28.8kBPH. And for a not-so-thin there are the Hattori (Seiko) ones, which beats like this and are strong work-horse that have the same finish and cost much less.

80h power reserve? I don’t really care about it: once it is more than 1 day it is ok for me.

This is an excellent article. Thank you. As a recent watchmaking school graduate, these topics are valuable to us at the bench.

I take issue with the assertion that a $1,000 Mido is “my first watch”, as if it is a toy. Or indeed that those who buy one inevitably “aspire” to be collectors of more expensive pieces. Both statements are insulting. My favourite movement is the 7S26C. That does not mean I am either poor or ignorant.

I am not a fan of this movement too. It’s sounds more like cost cutting. Imagine you have one of these and accuracy is out, you need to send it back to their Swatch Group subsidiary to have it replace the whole balance wheel. Independent watchmakers won’t be able to regulate it or even get the replacement balance wheel to replace it.

At a time when people are working hard to get lead out of materials in which it was traditionally used, it is very disappointing to see Swatch Group using a leaded alloy in a something that traditionally has not contained lead – watch mainplates and bridges.

Sure the movement is sealed in the watch, but the watch will be serviced, and many of the parts are disposable, introducing lead into the environment.

Hi Gandor, and thanks for your comprehensive article.

Actually, I can’t be a fan of this new movement.

Slower rate, change in materials (mostly cheaper and some not environment-friendly) and difficulty/impossibility to regulate are not what I would call an evolution.

It looks more a commercial move to force watch repairer to replace the caliber rather than fix it (increasing the costs for the final user). For sure it is a commercial move to underline that power reserve is increased (while the rate -> precision is reduced).

Hopefully time will show I’m wrong, but for the time being I’d go better for a Miyota or Seiko movement. More reliable and let me say more honest.

Best regards,

slide68

All good points here but honestly the Infintesimal amount of lead in say 100 of the movts still wouldn’t hurt the ecology..at all really, in fact i doubt if anyone.could even measure the impact of well over 1k movts…just not enough quantity, better to use lead here than anywhere else say a car Frame. Lol

Lead is bad but in this Infintesimal amount it would take.well over 1k of these movts to cause any.isues so I think that bit is just neuomgd the pail at least to bring it up in any real.exo hurting way if we were taking frames of cars yep id be on board w you guys on this as the rest I AM just not the lead bit

My Seastar powermatic 80 has treated me nicely while I’ve had it. I’m fine with getting a whole new movement whenever I get it serviced. It’s been running at -2 seconds a day since I’ve gotten it. No complaints from me.

Not a fan here. I have a Rado captain cook with a powermatic movement in. Really jerky second hand, and 26 secs per day fast from new, and now after 3 months it’s nearly a minute fast per day. Don’t care how long it runs when I’m not wearing it, but I do care that it keeps such bad time.

My tissot seastar 1000 runs at about 0,25 sec/day! wich is really impressive.

I have never had such a precise watch in my life (I have owned many timepieces), and if i really want to find some neg, I would not mention anything about the movement (at the moment) In future I don’t know.

Congrats Tissot, top watch at affordable price

!

The new movements are definitely a little technical revolution: a free sprung silicone hairspring for under 1000 USD is really remarkable.

But on the other hand, the Swatch Group needed a new movement for economic reasons, since all patents and copyrights for the old movements 2824-2 and 2892A2 are over and now every manufacturer can legally copy those movements, i.e. no more or little profit for the Swatch Group for the old movements, which are still very reliable.

Any idea if they have fixed the weak hand winding gears that the 2824 was known for?

I understand that details matter to many when talking about watches, but I’m neither a fan nor hater of this movement. My personal priority in a movement is accuracy, and most reports I’ve seen indicate highly accurate timing right from the box. The laser regulation used by ETA seems to be effective in the great majority of movements; nearly COSC standard, if not within. I don’t need 80 hours of reserve, but it’s a good thing. I also don’t need 28,800vph, but this too is a good thing. This was simply a business decision by Swatch to move on from the public domain 2824. If my mechanical watch tells me the time accurately, I’m happy with the movement.

I just unboxed a new Tissot with this movement (silicium hairspring). It hasn’t gone on my wrist and it might not given the failure to meet 80 hours after a full hand wind and a +10 to +15 sec gain per day over the course of a dial-up run down. I got it because I’ve been happy with my factory regulated Hamilton Khaki Powermatic. But the field watch seems to be effected by the stray magnetism in our shop and my lab more than I expected. I heard the misgivings about factory regulation and my watch maker won’t/can’t regulate it so I’m left pondering going back to quartz for work.

The beat of a movement is everything. How do you instantly tell the difference between a fake Rolex and a real one? 99% of the time the fake one beats at 21,600 with a cheap movement. Anyone can spot the difference between a second hand beating at 28,800 versus 21,600. I’ll take the higher beat rate any day. Lowering the beat rate seems to be a Swatch Group thing. Even Omega Co-Axials beat slower now at 25,200. If you don’t want your automatic watch to wind down, put it on a watch winder.