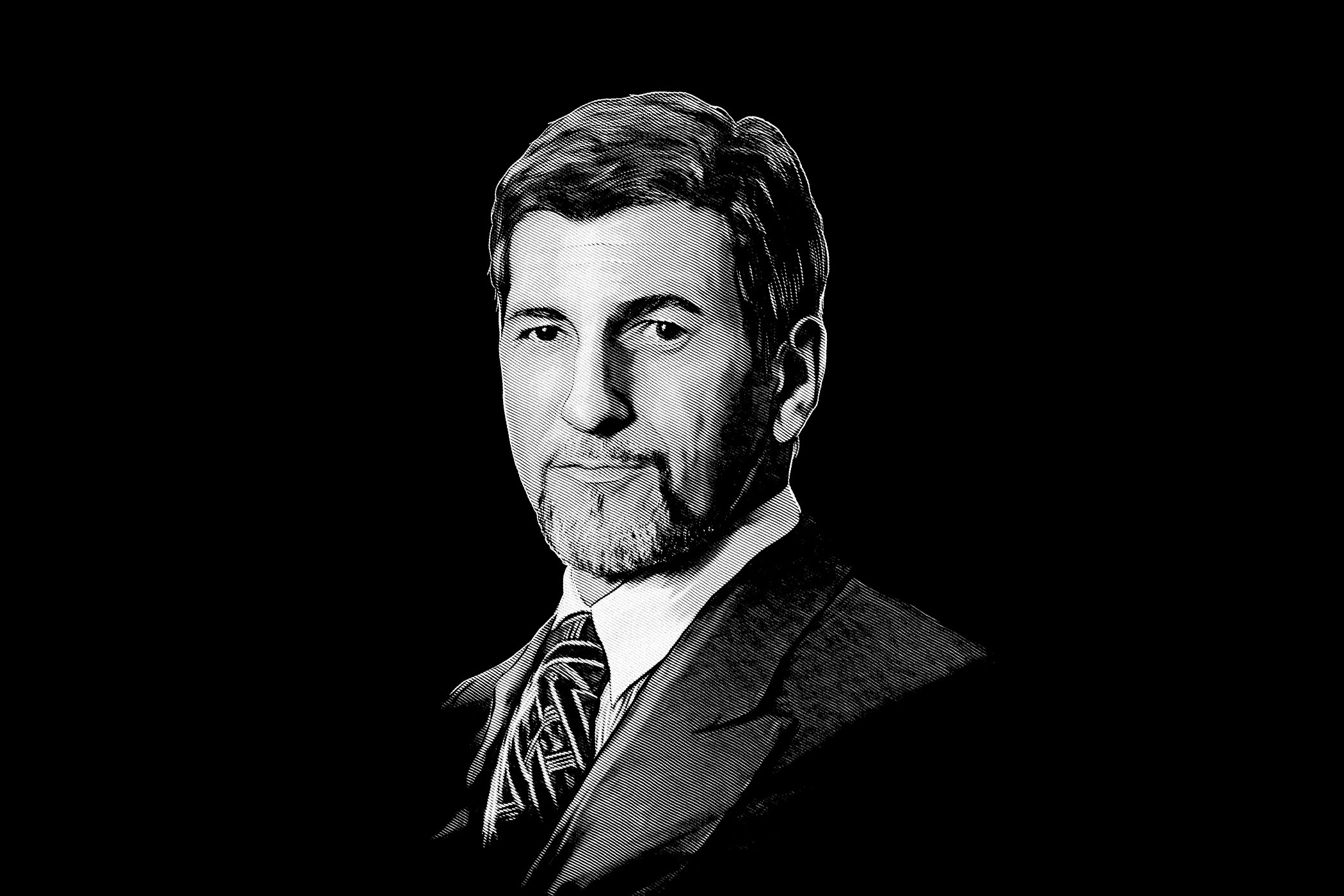

20 Years Later, Remembering Günter Blümlein and his Outstanding Contributions to the Watchmaking Industry

In honour of a man who was instrumental in generating a renewed interest in mechanical watches.

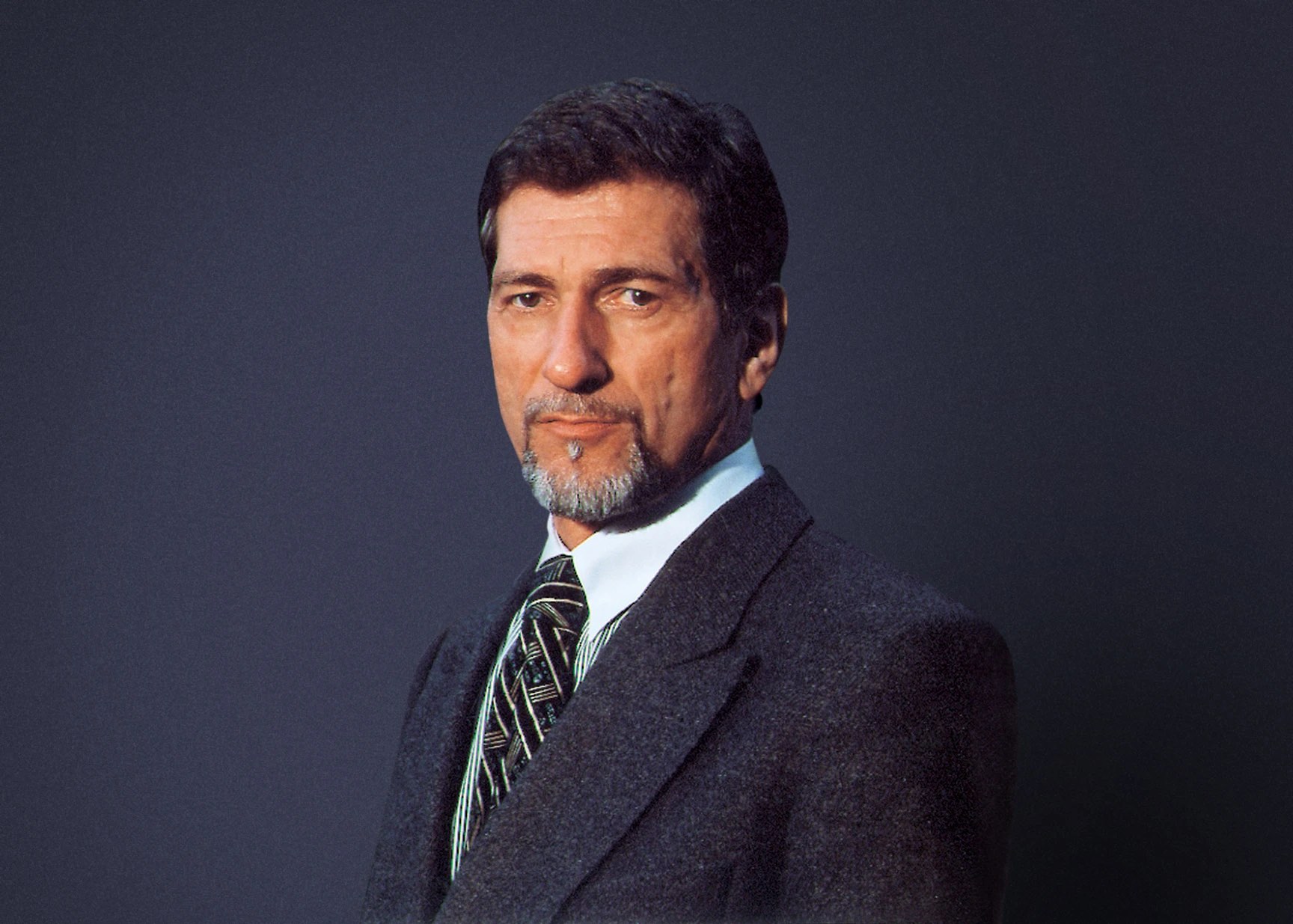

The watchmaking industry, before being a story of products, is first and foremost the story of women and men devoted to conceiving and producing some of the most delicate and yet unnecessary objects we can imagine. If all must be considered, some names resonate stronger, mostly for the impact they have had on this industry. You can, for example, think about A.L. Breguet and his influence on mechanical watchmaking. Or about Nicolas G. Hayek and how he’s been instrumental in staging the comeback of “Swiss-made” watchmaking. One of the names you can add to this list is, without a doubt, Günter Blümlein, a man who has done tremendous work to bring mechanical watchmaking back to the forefront, to restore watchmaking to the town of Glashütte and to shape the industry as it is today. And since Mr Blümlein passed away exactly 20 years ago, on 1 October 2001, it is the perfect time to remember one of the industry’s giants.

Remembering Mr Blümlein

The story of Günter Blümlein is linked to three of the most significant brands of the Swiss and German watchmaking scene: IWC, Jaeger-LeCoultre and A. Lange & Söhne, all under a division named LMH, which was crucial in shaping the Richemont Group as we know it today. And behind this successful rise of watchmaking were many women and men, under the lead of Mr Blümlein.

Günter Blümlein was born on 21 March 1943, in Nuremberg, Germany – not the most pleasant place to live, in all honesty. Despite being raised in a devastated country, during times of division in Germany, Blümlein successfully completed his studies and became an engineer. From 1968 to 1980, he worked for a German industrial group named Diehl (headquartered in Nuremberg, Germany), owner of the brand Junghans, one of the largest and most significant names in the German watchmaking industry (and once the largest clock and watch manufacturer in the world in the early 20th century). Blümlein became manager of the Group’s watch division, with a mission of restructuring the watch branch.

Following this experience, Blümlein moved to VDO Schindling AG, another German company that specialised at the time in speedometers and car instruments. In 1978, VDO purchased two important Swiss watch manufacturers: IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre. Thus, in 1980, Blümlein became the head of a newly created division, an umbrella company named “Les Manufactures Horlogères” (or LMH). Blümlein was also behind the restructuring of JLC, as he made sure VDO could buy out 20% of the company owned by a local bank and 25% owned by Vacheron Constantin. Right after, 40% of the company was sold to Audemars Piguet, a manufacturer that relied on JLC’s resources for some of its production.

The legend comes back to life” were the first words of Blümlein at the launch of A. Lange & Söhne in 1994

Another important achievement of Günter Blümlein’s was his involvement in the resurrection of German watch manufacturer A. Lange & Söhne, together with the Lange family, right after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The three companies were all directed by Blümlein under the LMH umbrella, part of the VDO/Mannesmann Group. Things would remain this way until Mannesmann was acquired by Vodafone in 1999. The new owner was ordered to restructure the group and to put VDO and watch activities up for sale. Blümlein had an important role in the negotiations, leading Richemont Group to be the new owner of LMH, and thus of Jaeger-LeCoultre, IWC and A. Lange & Söhne.

Günter Blümlein was crucial in this transition and in the integration of the brands into this new group. He passed away on 1 October 2001, after a brief but fatal illness, at the age of 58.

Blümlein and IWC

Looking at his curriculum vitae is one thing, but looking at what he has done for the industry and the three watch brands he oversaw for a large part of his career, starting with IWC or International Watch Company AG, Schaffhausen, is quite another.

When recruited by VDO at the age of 38, Blümlein, as the boss of a VDO subsidiary called Les Manufactures Horlogères, was asked by the German group to oversee two recently acquired companies, IWC and JLC. It is worth mentioning that we’re talking about one of the most challenging eras for the traditional watchmaking industry, which was still suffering from the competition of quartz, digital and electronic watches from Asia. If in today’s world mechanical watchmaking has been reinstated to its former glory (or at least to an undeniable level of success), this wasn’t the case at all in the early 1980s. Back then, mechanical watchmaking was dying. But some men, Blümlein included, thought there was a future for this traditional industry. And in this instance, Blümlein was instrumental in the comeback of mechanical watchmaking.

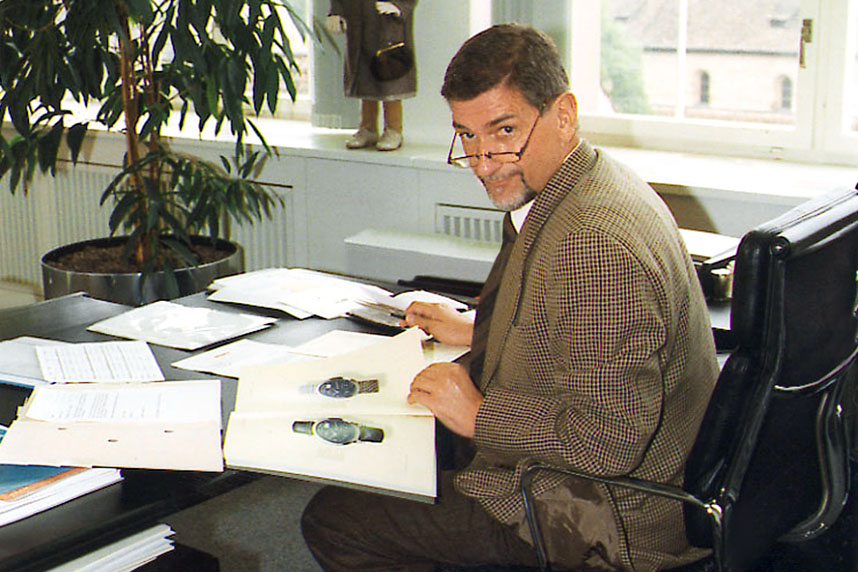

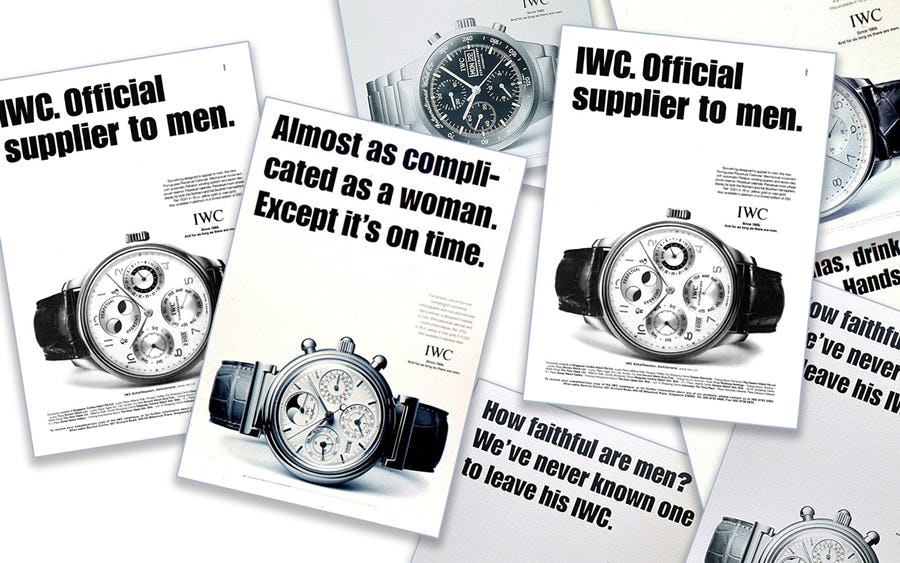

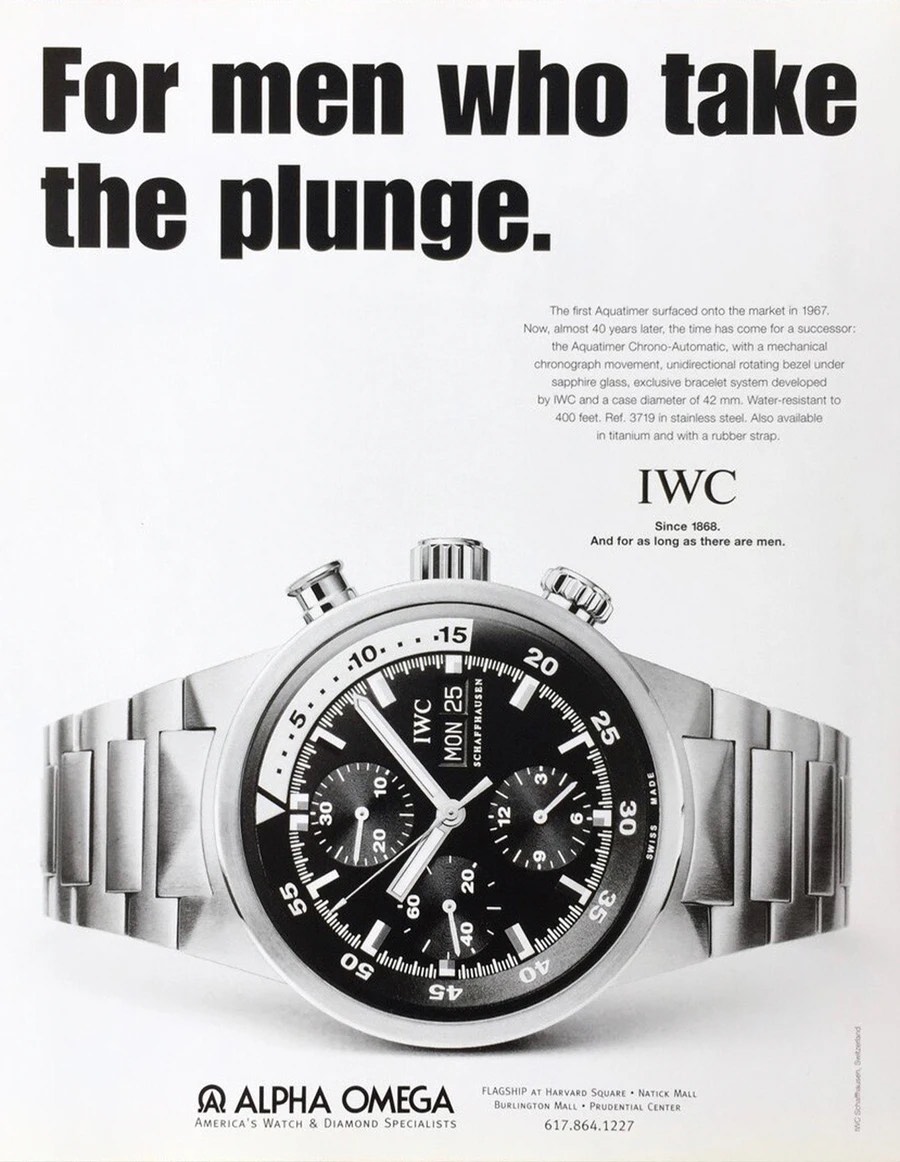

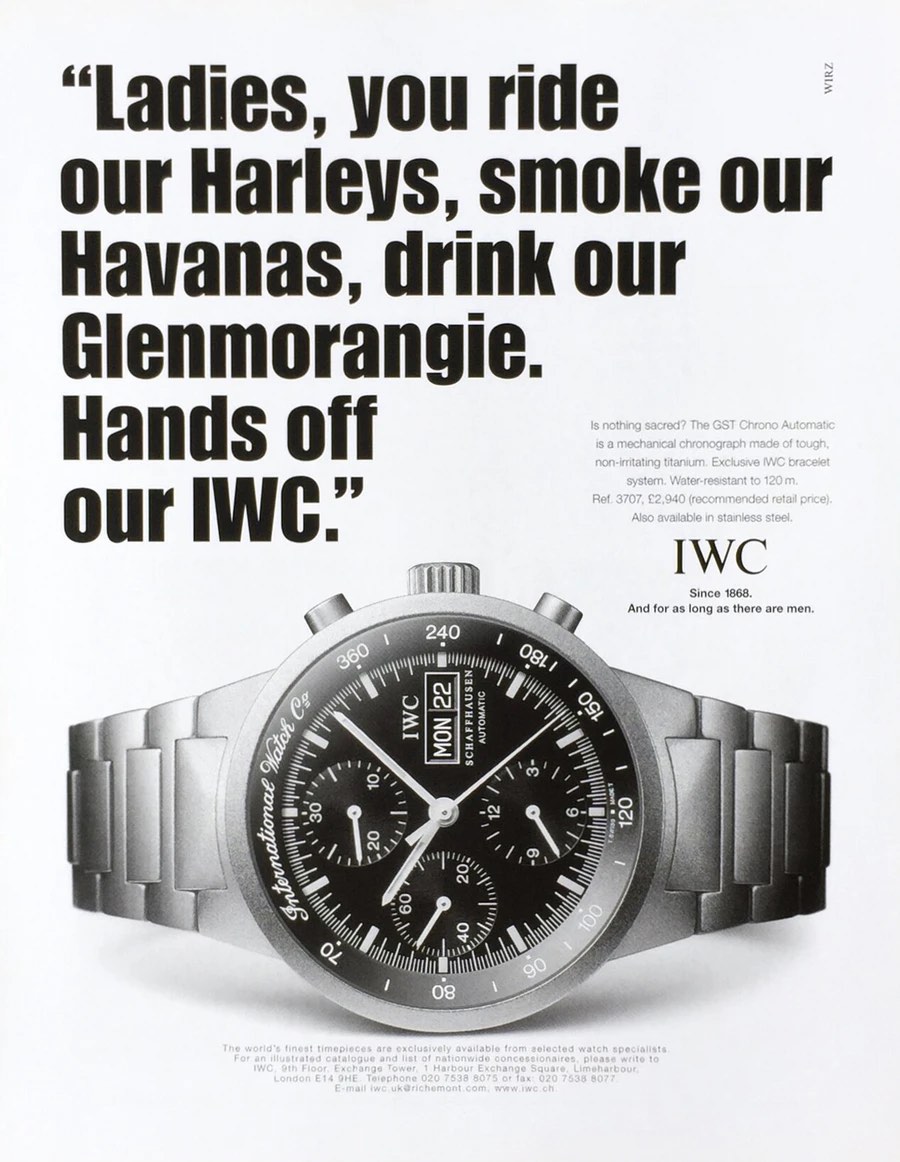

Upon arrival at VDO Schindling AG, Günter Blümlein’s first task was to restructure IWC. He focused his entire attention to revive this century-old manufacture located in the German-speaking side of Switzerland to its former glory, with a very clear and very personal approach. He wanted to “put an end to watchmaking boredom“, he once said, and for that, he applied his signature style: a clean, no-nonsense approach to watchmaking, ultra-focused with clearly defined collections and a certain sense of humour in advertising campaigns. Tag lines like “IWC. Official supplier to men“, “Almost as complicated as a woman, except it’s on time“, or “Ladies, you ride our Harleys, smoke our Havanas, drink our Glenmorangie. Hands off our IWC” appeared on these typically 1980s, masculine-toned adverts. It would simply be impossible today, but it worked back then.

Blümlein’s idea for IWC, a company renowned for its sports and military watches, was to attract a new audience. Not the typical over-40 traditional seasoned collector. The idea was to offer younger, more active, more adventurous potential clients a watch with a clear message, a bold style, a mechanical movement and a specialised function. This new strategy included teaming up with Porsche Design and creating several new collections, as well as important innovations in terms of watchmaking and materials.

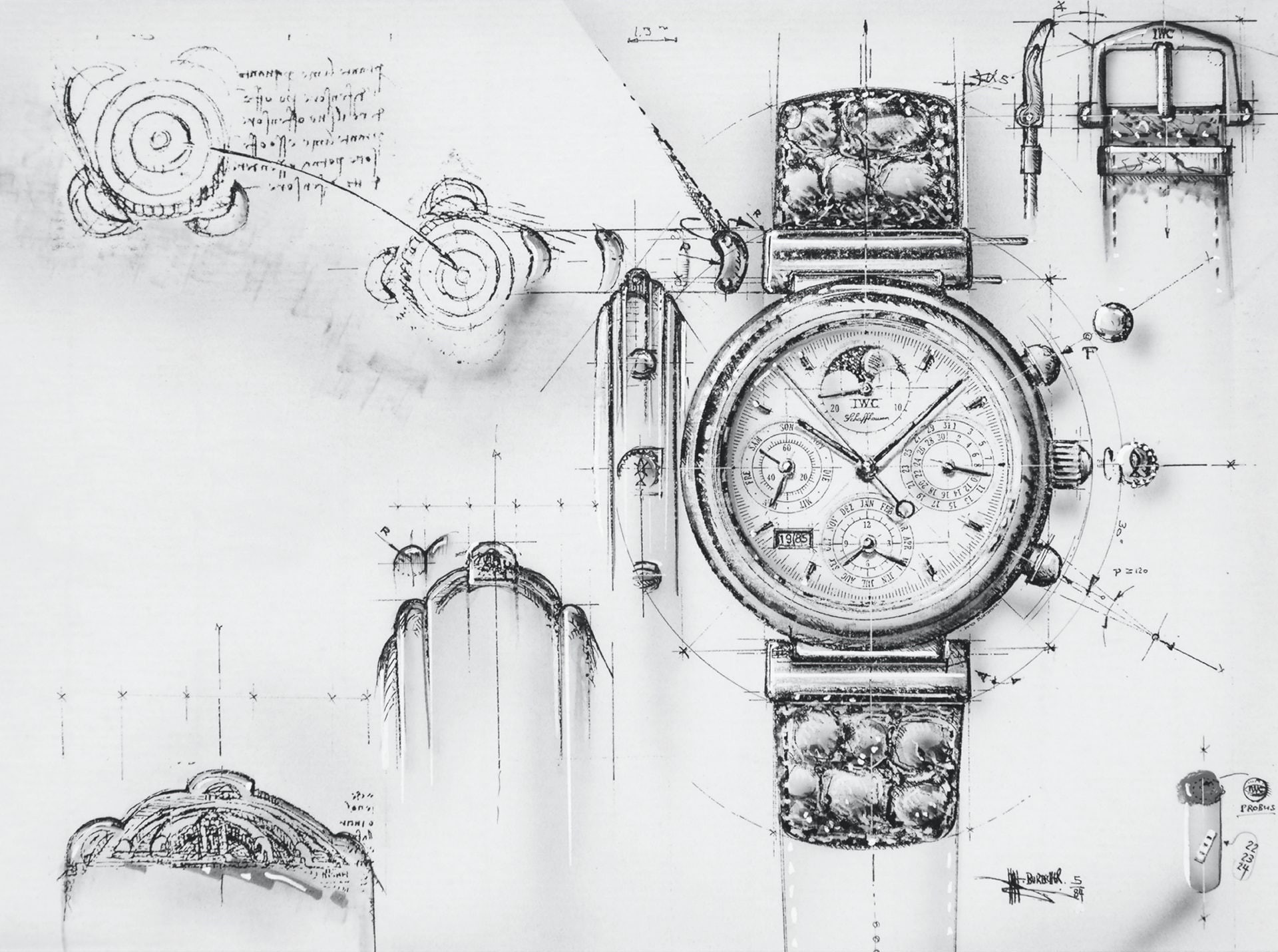

Following the PD x IWC connection, which increased the attractivity of the brand among car enthusiasts, Blümlein gave the Portofino collection a twist. Also, during the mid-1980s, he combined the best of watchmaking with innovations and free-spirited designs. And it started with the all-important 1985 Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar Chronograph wristwatch with a QP module developed by Kurt Klaus and adapted to a Valjoux base calibre. Not only was it as complex as models produced by industry heavyweights, but it retailed at a fraction of the price, allowing a wider audience to rediscover traditional watchmaking. With this watch, Blümlein also introduced innovative materials and created the first ceramic cases… Once again, something bold and different.

Under the direction of Blümlein, IWC also revived one of its most important collections, the Pilot’s Watch. This time with the help of Richard Habring, who developed a rattrapante module to be added to a Valjoux base, IWC laid the foundations for what is today its most recognisable collection. And of course, Blümlein was behind the renaissance of the all-time great Portugieser collection, as well as the creation of the GST line. In short, some of the greatest watches ever produced by IWC in recent history. And once IWC was on track, Blümlein’s next project was to dust off La Grande Maison…

Blümlein and Jaeger-LeCoultre

Contrary to IWC, Jaeger-LeCoultre was not a brand that could be transformed as easily. Far more traditional, far more focused on watchmaking capacities and manufacturing operations, the task of Blümlein was drastically different at JLC. In addition to being a watchmaking brand, with its eponymous models, JLC was then a large provider of movements to brands like Vacheron Constantin, Audemars Piguet, Patek Philippe and others.

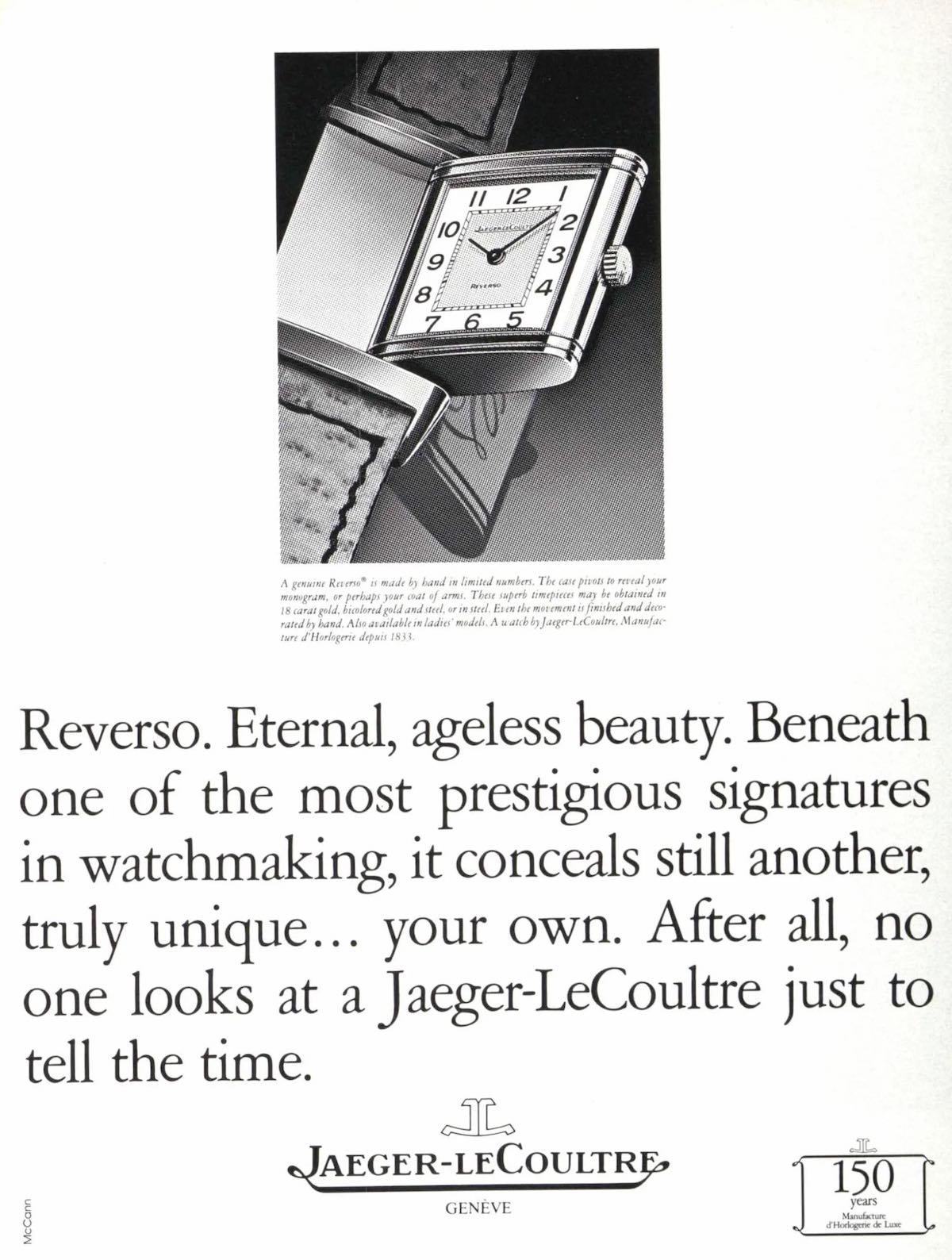

What worked with IWC couldn’t work with the more traditional profile of Jaeger-LeCoultre. Blümlein changed tack and capitalised on existing assets, rather than starting from a blank page. And the focus for Blümlein was on one of the oldest and most significant watches of both JLC and the industry, the Reverso, which he revived and made the cornerstone of the brand’s portfolio. Indeed, it is hard to believe today, but the Reverso was out of production for most of the second part of the 20th century (with rare exceptions during the 1960s).

The Reverso became an instant hit for Jaeger-LeCoultre, so much so that by the end of the 1990s, the collection accounted for 65% of the brand’s production. This allowed two things for JLC: one, having a strong model that was instantly recognisable and immediately affiliated to the brand, giving JLC an incredible aura; second, it gave the brand the necessary resources to revive its traditional Haute Horlogerie credentials and to invest in the development of some of the most advanced movements and rarest of complications. By the turn of the 2000s, the interest in traditional high-end watchmaking was at an all-time high and growing, and Blümlein decided to use JLC as his vector to meet the rising demand. This strategy resulted in the creation of the Master Control series – watches with rigorously tested and highly accurate movements – and the invention of displays such as the Geographic, the multiple Alarm watches (Memovox) or masterpieces such as the Grand Réveil of 1989 (combining a QP with the brand’s signature alarm function).

But in 1990, an event changed the face of Europe forever, an event of particular importance for a man born and raised in divided Germany: the fall of the Berlin Wall. Blümlein was now on a mission, which might have been highly personal, to revive traditional Saxon watchmaking in the town of Glashütte.

Blümlein and the resurrection of A. Lange & Söhne

Günter Blümlein ranks among the major rejuvenators of the Swiss and German watchmaking industries. With the restoration of IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre accomplished, as well as making major contributions to the renaissance of mechanical watchmaking in general, Blümlein decided to bring back the idea of “Made in Germany” watches as a true hallmark of quality. Following German reunification, which formally took place on 3 October 1990, things were possible. During these times of division, A. Lange & Söhne had been under state ownership and absorbed into Glashutte Uhrenbetriebe, following its seizure by the state in 1948.

But in 1990, and together with Walter Lange, Blümlein laid the first stone of what would become one of his most outstanding achievements, the revival of the A. Lange & Söhne brand, essentially from scratch. It took four years and about EUR 20 million to develop an integrated corporate, product, and marketing concept that would later propel the name A. Lange & Söhne back to the pinnacle of watchmaking, and not only in Germany.

In 1993, Blümlein and Lange set the cornerstone for the restoration of the Lange I building (the Lange IV manufacture was inaugurated in August 2015), the historic site of the brand. And inside these walls, Blümlein set out to make some of the most complex watches possible, with the highest level of quality.

As a newcomer, we cannot afford to show any weakness. Our products have to be perfect down to the last detail” Günter Blümlein

He is also known for saying: “The Swiss make the world’s best watches. So do the Saxons.” And a quarter of a century later, we can say, without a doubt, that he was right. Without Günter Blümlein, Glashütte would not have become the centre of the German watchmaking industry again. On 24 October 1994, at the Dresden Royal Palace, Günter Blümlein, Walter Lange and Hartmut Knothe unveiled the inaugural collection of the new A. Lange & Söhne manufacture. Alongside the Saxonia and the Arkade were two extremely important models created by Blümlein.

First is the Lange 1, an emblematic model that still today perfectly encapsulates the brand’s mission in 1994, revealing a combination of elegance, typical German design, a signature off-centred dial architecture, the first outsize date in a regularly produced wristwatch, and a movement decorated with extreme attention to detail.

The second was the Tourbillon “Pour le Mérite”, the most complex of the four inaugural watches, and one of the most complicated wristwatches available at the time, with its combination of a tourbillon regulator and a fusée-and-chain transmission, a constant-force mechanism that had never before been integrated into a wristwatch.

In 1999, A. Lange & Söhne presented a watch (and a movement) that showcased Blümlein’s legacy in terms of product development: the Datograph. The idea of an in-house, Haute Horlogerie chronograph was simply unique in the industry, as none of the large players of the era could do the same. “The legend comes back to life” were Blümlein’s first words when the company was back on track… And indeed, it is still going strong.

Without Günter Blümlein, A. Lange & Söhne would no longer exist – and Glashütte would not once again be the centre of German fine watchmaking.” Walter Lange

From LMH to Richemont

In 1999, the watch division of VDO Les Manufactures Horlogères was highly successful (at least relative to the competition back then), with an estimated turnover of over CHF 300 million, according to Le Temps. However, in 1999 Vodafone acquired Mannesmann (which acquired VDO before that) and immediately put VDO up for sale. A highly valuable asset in a rising market for watches, this announcement led to an intense bidding war between PPR (to become Kering) and LVMH. The outcome was that none of these groups was able to acquire LMH. This would become the property of the Richemont Group and Johann Rupert. The Group did things discreetly and approached Audemars Piguet to acquire its 40% participation in Jaeger-LeCoultre for CHF 280 million. And with this participation in the books, Richemont enjoyed a favourable position for acquiring LMH, which was finalised on 21 July 1999, for a price of CHF 2.8 billion.

When I met Günter Blümlein for the first time, I knew he was the answer to all questions related to watchmaking.” Johann Rupert, Richemont SA

Günter Blümlein oversaw the sale of LMH and the transition into the Richemont Group, incidentally becoming head of its watch division. A man known for his 80-90 hour work weeks and his strong character, he “was aware of his great abilities, and therefore his sometimes explosive personality was not entirely devoid of vanity. Dialogue with him took strength, courage and, above all, very good arguments. Blümlein was always open to them,” said Peter Chong of Deployant on remembering him.

Günter Blümlein passed away at the age of 58, on 1 October 2001, after a brief but fatal illness. He leaves behind an incredible legacy in the watchmaking industry; he was instrumental in the renewed interest of the public in mechanical watchmaking, and he mentored women and men such as Jean-François Mojon, Richard Habring, Robert Greubel, Jérôme Lambert, Anthony de Hass and Max Büsser. He will not be forgotten.

A few words from those who knew Günter Blümlein and worked with him

To complete this retrospective, we’ve asked some of the industry leaders who have been working with Blümlein to address a few words on this important man.

Anthony de Haas, Director of Product Development at A. Lange & Söhne

Mr Blümlein was an impressive, charismatic man with loads of positive and inspiring energy. He had a deep knowledge about watchmaking, technical understanding but not only that, he was a real genius in product marketing. A great visionary man! He had a big influence on my professional life. When I was about to leave IWC to APRP, he tried to convince me to come to A. Lange & Söhne, for me not an option at that time since I signed a contract. Anyhow, this would have been the moment he “infected” me, in a positive way, of course, with the “Lange virus”.

I will never forget this moment when he showed me a Datograph prototype trying to convince me. You can imagine what that watch did to me… It is a big honour for me to continue the work he, and Mr Lange, started in 1990; today we still work with the same philosophy and spirit as in the beginning.

Maximilian Büsser, founder of MB&F

There is so much I would love to tell you about Mr Blümlein. I owe him so much.

Günter Blümlein was, alongside Henry-John Belmont, the most important mentor figure in my professional life. During my seven years at Jaeger-LeCoultre (1991 to 1998), I was constantly in awe. His super sharp strategic thinking, his unquenchable passion for high-end watchmaking, his capacity to reinvent himself and the companies he was heading and his aptitude to explain the most complicated ideas into simple words. And, of course, how he recreated the 20th and 21st century A. Lange & Soehne from scratch. A masterclass on reinvention never equalled in our industry since.

Two anecdotes amongst so many come to my mind. The first was a five minute “sparring battle” between him and me (young junior product manager in my mid-twenties) on some future product characteristic during a meeting when, at some point, he stopped me in my tracks by a “Mr Büsser! Creativity is not a democratic process” BOOM! Definitely amongst the top three most important pieces of advice in my life.

The second is Baselworld 1999, I have just taken over Harry Winston Timepieces, which was in a very dire situation. I’m 31 years old, feeling completely inadequate, battling to try to save the company against extreme headwinds. The only person who came to see me from my JLC days is Günter Blümlein. To my great surprise, he took a few minutes of his insane schedule to walk up to the first floor and say hello. I was a desperate train wreck, and his words, “I am sure you will do great. If someone can save this company, it’s you“, probably saved me from falling off the cliff. Bluemlein had never given me any particular praise in my seven years at JLC – he could not have chosen a better timing for his first time. It was, very unfortunately, the last time I would see him. I still sorely miss him today, twenty years later.

Richard Habring, Co-Founder of Habring²

Günter Blümlein liked sayings. We do once in a while find ourselves (Maria & me) repeating some of those. This one he liked: Was interessiert mich mein Geschwätz von gestern. (1000-zitate.de). It’s in the sense of “Who cares about the bullshit I said yesterday!” Mr Blümlein used it repetitively, and in the end, his reminder was only: “Remember Andenauer!”

Another one was “Der Wurm muss dem Fisch schmecken!” in the sense of “the fish needs to like (and bite) the worm, (not the fisherman)!” He liked to use it when he was unhappy with a product and or its communication (I used it recently towards a young German watchmaker who spend some days with us and talked about his product ideas for the future… laughs)

I believe he considered himself (even at the peak of his career) more of an engineer/technician than the leader/visionary/marketing genius we see today. The product (and its technicalities) was always first, then came marketing, communication, etc…

Mr Blümlein liked unconventional solutions, directions, approaches, and his leadership style was not necessarily democratic. It took me some time to realise how much (internal) opposition he must have been confronted with during his career. I remember lunch and dinners (in Schaffhausen and Glashütte) when he was invited at short notice just to spend some time to talk on both technical/products as well as business/politics. Especially in Glashütte, I often had the impression he liked to escape Knothe’s stiff structures.

I must have somewhere a handwritten (on ALS-paper) note from him with comments on Mr Knothe’s meeting-culture: “If you don’t know what to do next, you set up a working group” and “It is not far from the round table to the long bench“.

1 response

Quite some guy. I like Richard Habring’s comments, particularly recalling the fish/fisherman saying. A watchmaker’s axiom, no doubt.